- Home

- Laura Marello

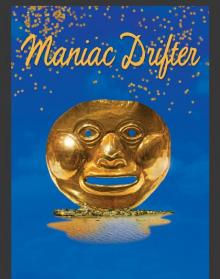

Maniac Drifter

Maniac Drifter Read online

Essential Prose Series 125

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Acknowledgements

About The Author

Copyright

for my mother

Provincetown,

Cape Cod,

Summer 1985

Chapter One

Friday

I woke up Friday morning in bed with a man I didn’t know. Of course I had seen him around town. His name was Getz. He was thin and muscular, had fine features and a sexy, angular face that promised mystery. When I had asked about him, everyone in town had warned me that Getz was a coke dealer. Almost everyone who had been in Provincetown for more than ten years had dealt drugs at one time or another. They were just mad at Getz because the Zanzibar had been the best hangout in town in the seventies; he had been the manager and bartender. They blamed him for it closing down. They said he skimmed money, embezzled it, lost it, mismanaged everything. Now he was a lobsterman.

But a lot of people had done that. The scenario went like this: a guy came to town, dealt dope until he had enough money to start a restaurant, made a lot of money at the restaurant, but got greedy and kept dealing. Then he began to throw his weight around in town politics, leaning on people, making them mad. That was usually when the Feds came in, shut his place down until he paid his taxes, or indicted him on a drug traffic charge. Provincetown was like an ongoing B-movie; the restaurant owners, bar owners and bartenders were the movie stars. One star got indicted about every five years or so, always through a similar chain of events. This raised him from star status to Town Hero.

I’m in a movie, I thought as I sat up in bed. This town’s a goddamn movie. That’s when I looked around the room and realized I wasn’t at home.

I walked out onto the porch and saw that a flying buttress in the shape of a voluptuous woman was nailed above the door lintel. I knew right away that I was at the Figurehead House. I could see the bay on the other side of Commercial Street, the gutted Ice House down the hill on the water side. It was sunny, and a slight breeze blew off the water. No one was awake yet; the tourists had not come in from up-Cape. I walked down the hill toward home.

I lived on the top floor of a white house on Bradford Street that had been converted into apartments. It would have been impertinent to lock the door. A black leather jacket and felt fedora were hanging on the crank handle to the skylight. Harper Martin, the owner of these sartorial gems, was asleep on the day bed in the kitchen. I had never woken up in the morning and found myself in bed with Harper Martin. I wondered if it would be different with him, if I would be able to remember.

Harper always played the part of the friendly sleuth, with his jacket and fedora, his jaunty walk and manner. But was he really a sleuth or just acting one? I could never determine. He drove a silver Corvette that said Maniac Drifter on the bumper, and had wooed his last girlfriend by singing her rock songs across the parking lot of Days Studios, where they were both painters-in-residence. He wrote the tunes himself. “Is-a-bel-la! The stock market crumbles when I speak your name!” was the chorus to one.

The skylight was cranked all the way open; I stuck my head out and looked at the bay. I had a view of the water between the Ice House and the neighboring roof. A few lobster boats and trawlers headed toward the breakwater. The gulls whizzed past my head. This apartment was in the gull zone, intruding on their airspace. They liked to dive-bomb anyone who stood under the skylight, and then pull out at the last minute.

“Hey,” Harper said. The noise of the gulls must have woken him up.

“French toast?”

Harper climbed out of the day bed and slipped his chinos on, then his white shirt and string tie, then he sat on the bed and put on his black socks and wing tips.

I grilled the French toast while he set the table, humming as he walked around the kitchen. Suddenly, as he was folding a napkin, he belted out: “Romance without finance is a nuisance (you ain’t kiddin’ brother!). Mama, Mama, please give up that gold.” He came up behind me at the stove and looked over my shoulder. “Wanna come to El Salvador with me and break up marriages? You can chase after the husband; I’ll go for the wife.”

For a moment I thought he knew about my trouble and was making light of it, but he couldn’t know. I hadn’t told him, and it wasn’t simple enough to guess.

“See what I care,” he said. “Wanna be the lead singer in my New Wave band?”

“Bring me the plates,” I said. He brought them. I slid the French toast on to them. I asked him why he smelled like a lobsterman.

“I was sitting next to one last night,” he said. “The lobsterman’s name was Getz.”

“How do you know he is a lobsterman?”

He poured a dollop of syrup on his French toast. “Hey, babe, I may be from Los Angeles, but after two years in this joint I can tell the Yankees, Portuguese, lobstermen, artists, hippies and gays apart.”

When we had finished eating, Harper took the empty plates to the sink and ran water over them. He bellowed: “You’re so good and you’re so fine, you ain’t got no money you can’t be mine, it ain’t no joke to be stone broke, Baby, Baby, I’m not lying when I say that — ”

“Why’d you spend the night on the day bed?”

“I’m running from the law.” He put on his jacket and fedora, tipped his hat, bowed graciously, and shut himself in the bathroom. I licked the rim of the syrup bottle. I could hear the shower running and Harper singing, “You must remember this, a kiss is just a kiss, a sigh is just a sigh. The fundamental things apply as time goes by.”

Harper was right about his categories: Yankees, Portuguese, fishermen, artists, hippies and gays — that was Provincetown. The Pilgrims landed first, and settled out on Long Point, a spit of sand that curled to a tip out past the edge of town. You would have to walk through marshes or over a breakwater to get to it now. It was too cold and windy for them there, so eventually they went to Plymouth. But people kept coming and settled out on Long Point, to fish mainly, and eventually some moved into town. When no one lived out on the Point anymore, they brought the houses into town and affixed blue historical plaques to them.

After the Yankees, the Portuguese came over, also to fish, and they had been here ever since. Now they lived on the northwest side of town, behind all the tourist traffic on Bradford Street, just beyond Shankpainter Pond, in modest houses where no one would bother them.

The artists first came in the 1880s; Charles Hawthorne was the most famous of the group. They came again in the 1920s, among them were Edwin Dickinson, Eugene O’Neill and the Provincetown Players. Dickinson lived in Days Studios; the Art Association and Beachcombers were formed. In the thirties and forties the Abstract Expressionists came from New York; Motherwell and Frankenthaler used the barn at Days Studios. Cosmo and his group of Rhode Island painters joined the Art Association and Beachcombers. Galleries sprung up, each with its allegiances and rivalries. Now, in the eighties, Cosmo and his circle remained in town, while most of the Abstract Expressionists summered in the Hamptons, except for Motherwell, who had stayed in Provincetown and moved his studio from Days into his home on the East End. Days Studios was now used by the young up-and-coming painters like Harper Martin, most of whom came in from New York for winter residencies. Some stayed on when summer came.

The hippies came over in the sixties and they were the attraction for that time, Provincetown being prone to fads, being Mecca for whatever fad came. But some of them stayed and now they did things around town that suited them. Angelo Fontana was a whale and seal expert. Other hippies that had stayed worked as leathersmiths or bartenders, one had become an orchid specialist and park ranger, some of th

em learned how to fish, some dealt drugs or worked for the nonprofit radio station.

The gays had been in town since the 1950s, but did not become really visible until the last ten years when their lifestyle became fashionable. Since Provincetown was the end of the road, with nothing beyond it, no one could come through on their way somewhere else. They could only come because they chose to. So the gays figured if people did not like their lifestyle, they could leave. And since they were the most disdained newcomers, nobody listened to them. While no one was listening, they made a lot of money. The women bought restaurants, bars and guest houses. They employed their own lawyer and real estate agent. The men owned bars, restaurants, clothing stores, hairstyling salons, gourmet food shops. They also had a real estate agent of their own. The gays controlled most of the nightclub acts in town; there were two main transvestites, Montana Devon and Gerty. The women had this incredible French Canadian singer named Christianne who was a combination Edith Piaf and Judy Garland in a tuxedo. She sang duets with her wife, Paula. And most everyone slept around — the hippies, the painters, the gays. I liked it that way; it made my problem easier to conceal.

Harper reappeared in the kitchen a half hour later, fully dressed, with his jacket and fedora on. He bowed gravely and thanked me for the use of my shower.

“No problem,” I said.

“Wanna run away to El Salvador with me?” he asked again. He had just returned from a trip to Nicaragua. When I had asked him why he went there, he said because it was “the happening thing.” I figured he would go to Poland or Lebanon or South Africa next, but El Salvador sounded practical.

“You never told me why you slept on the day bed last night,” I said. He would not ask me where I had slept, but it wasn’t out of a sense of propriety. It was as if he knew it was a dangerous subject, and should not be broached.

“I told you, I’m a fugitive from the law.” He opened the door. “Well I’m off. See you in a few minutes.” He bowed, and shut the door behind him.

On the way to the law office I wondered if Harper were just kidding, or really in trouble, wondered if he were acting the part of the sleuth or was really the sleuth, wondered if he were pretending to be in a movie or if he really was the movie. “This town is a movie,” I said out loud. “I’m in a goddamn movie.”

***

There were two law offices in town, but since I worked at the one which belonged to Ruth Allen Esquire, I called it by its generic name, the law office, as if it were the only law office in town, the way I referred to Cosmo’s as the restaurant and men referred to their wives as the wife. Ruth Allen had her offices on the bottom floor of her big white house on Commercial Street on the east end of town, near Getz’s Figurehead House.

Ruth was a small, robust woman with curly brown hair and sparkly black eyes. She had a keen intellect and a devilish curiosity, a sharp wit and hot temper. She was always full of energy, sexy and unselfconscious.

I knew the other town businessmen with movie star status would be at the Maniac Drifter investors’ meeting: Cosmo, Antaeus, Falzano. But I had not expected Raphael Souza to be there. I did not think Harper would want to approach him, or even know how. People were embarrassed by tragedy. They did not know how to act after it struck, what to say to the survivors. But there he was, Raphael Souza, sitting in Ruth’s office with the other movie stars, when I arrived 15 minutes late.

The Souza family was Provincetown’s version of the Kennedys. It was one of the most influential families in town. Jack Souza, 50 years old and the younger of the two brothers, was the president of Provincetown National Bank. The older brother, Raphael Souza, had been running a successful fishing fleet in town for 30 years, and was very influential on the wharf. For the past ten years he also owned the most popular gay bar and disco in town, the White Sands. He lived in the old family house, huge and white, on the west end of Commercial Street, with his boyfriend Tommy and his sheepdog Zac. Copies of Roman statues sat on the finely clipped front lawn. A flagpole stood near the gate; at sunrise Tommy raised the American and Portuguese flags on it, at sunset he lowered them. The eight-foot mesh fence that surrounded the property was entwined with honeysuckle vines. Some nights, on my walk home from Cosmo’s, I leaned against the fence, stuck my fingers into the honeysuckle, and watched the top of the house, where a blue light shone in the cupola.

Raphael Souza had been divorced despite the fact that the family was devout Catholic. In those days he sometimes left his fishing fleet to his captains and sailed down the coast to Newport with a pretty girl. When Jack’s daughter Julie was little, she had a lot of fun with Raphael and his daughter Annie on the boats, and seemed to prefer Raphael’s company to her own father’s. This caused bad feeling between the brothers. Their sister Elaine Barry, who was divorced and still lived in town, had tried to bring the brothers back together but nothing worked. A rumor circulated that Raphael was the biggest dope smuggler on Cape Cod Bay. Eventually Jack accused him of using their daughters to transact special deals in Boston, where they attended prep school and then college.

Once Jack had accused Raphael the disasters escalated, as if bringing the danger into the open had unleashed it. First Antaeus’ mother killed the Souzas’ mother in a hit and run accident. Raphael, being the oldest, inherited the family house. Just after he moved in, his daughter Annie was murdered in Boston by a dope dealer. Annie’s mother committed suicide. Raphael took a boyfriend, Tommy, into the house, saying that he would never go near another woman, all his women had been killed — his mother, his daughter, his wife — and that maybe it was his fault, maybe he had a King Midas curse with women, destroying them from greed. Jack never forgave him for bringing Tommy into the family house.

Raphael Souza had already attained movie star status by the time his mother was killed, so when his daughter Annie was murdered he became a Town Hero. With his wife’s suicide Raphael was elevated to the highest status possible in Provincetown: Martyr. Raphael even looked like a Christ figure, with his long, curly gray hair and full beard — only the cigars he and Tommy smoked ruined the image. But the locals didn’t care about the martyr status, they were in love with the idea that this family was Provincetown’s version of the Kennedys. They were handsome, glamorous, Catholic and doomed. Didn’t a suicide, murder and fatal accident compare to assassinations, plane crashes on the Riviera and Chappaquiddick? The glamor of the Souzas was smaller scale certainly, they were not rich and the brothers were not Presidents, but the Provincetown locals liked to imagine that the big white house with the cupola, the pristine lawn with its statues, was like the Kennedy compound at Hyannis Port; and the brave, handsome brothers who were plagued with accidents and tragedies, due in part to their own weaknesses, were simultaneously charmed and hexed the way the Kennedy brothers had been.

“Sorry I’m late,” I said when I entered the investors’ meeting. Ruth was ensconced behind her desk, talking on the telephone, presiding over the movie stars. She always felt magnanimous toward me at these moments, when large groups of people were watching. She waved her free hand in the air as if to say, No problem, and pointed to the empty chair where she meant for me to sit down.

The chairs were arranged in a half-moon shape facing Ruth’s desk. It looked like a United Nations meeting, or a panel of experts. Each investor had a black vinyl three-ring binder in his lap. I sat down next to Harper. While Ruth talked into the phone and tapped numbers into her adding machine, Harper bounced one leg up and down, causing his fedora to jump in his lap. Ruth hung up the phone. “Okay,” she said, “the bank’s confirmed my figures.” She rummaged through some papers.

“I won’t read through all the Articles of Incorporation because most of them are standard. As you know, the corporation will be called Maniac Drifter Inc., and Harper will act as the officers: president, vice president, secretary and treasurer. The added clause concerns each investor’s share, and the privacy of corporate activities. It says: Article VIII Investors agree to grant officers of Maniac Drifter I

nc., to wit, Harper Martin, complete privacy as to the nature of the corporation’s activities. An Investor may audit the corporate books only when said investor’s percentage of return has dropped below the agreed upon rate, or the corporation’s treasurer, to wit, Harper Martin, is late by more than thirty days in his monthly return payment. Okay, Kate is going to pass out these envelopes.”

Ruth handed them to me.

“The sheet inside states your amount of investment, percentage of return and calculated monthly payment. These will be listed in Appendix A of the Articles. I was just on the phone to Jack at the bank and he verified the figures, so they should be okay.”

I passed out the envelopes to the all-star cast there that day, the best and brightest of the movie-star status in Provincetown, all together in one room. It was like ensemble acting. The office was riddled with the widest range of personal, legal and financial disasters imaginable. Of course Cosmo had had an affair with his partner’s wife, and Raphael suffered from a female trinity: his daughter was murdered, his mother run over, and his wife had committed suicide. But Antaeus and Falzano also had tragic histories. You could not achieve movie star status in Provincetown without it. Antaeus was known for the events five years before which had raised him temporarily from movie star status to Town Hero. He was indicted on Federal drug traffic charges in the summer, and in the fall his mother killed Raphael Souza’s mother in the hit and run auto accident. Then his Bad Attitude Cinema was mysteriously arsoned. Locals referred to that incident as the Fall Arson Festival.

Giulia Falzano had her own tragedy. She owned Paradiso’s, the women’s disco, when Christianne moved down from Montreal looking for a singing job. Falzano hired her to perform Edith Piaf numbers as a second act to Paula, Falzano’s wife and business partner. By the third summer Christianne and Paula were singing together. They worked up a routine and went on tour alone that winter. They came home lovers. Falzano had to break up another long-standing relationship, Anna and Jill, to replace Paula. Jill, in turn, disrupted a long-standing relationship to get Esther. Falzano had a sense of humor about it; she called this Dyke Dominoes.

Maniac Drifter

Maniac Drifter